You’re in a kickoff meeting. Someone suggests, “Let’s find out everyone’s learning style first. Then we can tailor the training.”

Heads nod. It sounds thoughtful. It sounds learner-centered.

And you feel that small, nagging voice: Is this actually a thing?

If you’ve been in L&D for a while, you’ve probably been in that room.

It felt like good practice.

Here’s the hard part:

Decades of research say it doesn’t actually improve learning.

This is not a “you’ve been doing everything wrong” moment. It’s a “the field has moved on—and now we get to move with it” moment.

Let’s unpack why learning styles are so tempting, what the research really says, and what to use instead that does help people learn.

Why Learning Styles Feel So Right

The core promise of learning styles is simple and attractive:

“If we know how someone learns best, we can design just for them.”

Who wouldn’t want that?

It also fits a story we like to tell about ourselves:

“I’m a visual learner.”

“I’m an auditory learner.”

It sounds like knowing your Hogwarts house. It gives you an identity.

From an L&D point of view, it can feel:

Human.

Personalized.

Modern.

The problem is that the evidence never caught up with the marketing.

Large reviews—like Coffield et al. (2004) and a widely cited paper from Pashler and colleagues in 2008—have looked for a “learning styles boost” over and over again.

They didn’t find it.

What the Research Actually Tested

Researchers didn’t just ask, “Do people have preferences?” That answer is easy: yes, they do.

They asked a tougher question:

“If we match instruction to a person’s preferred learning style, do they learn better than if we don’t?”

This is sometimes called the “meshing hypothesis.”

To support learning styles, we’d need to see a clear pattern:

- Label learners by style (visual, auditory, etc.).

- Teach some people in their preferred style and some in a non-preferred style.

- See better test results for the “matched” group.

Across many studies and reviews, that pattern just doesn’t appear.

Learners often feel better when things match their preference. But when you look at performance—recall, problem solving, transfer—the “style match” doesn’t provide a consistent boost.

The careful conclusion from these reviews is:

There is no strong evidence that designing training to match learning styles improves learning outcomes.

That’s the myth-busting part.

Now let’s talk about what to do with it.

The Hidden Cost of Chasing Styles

You might be thinking, “Okay, fine. But what’s the harm? Isn’t it at least harmless?”

Not always.

Here’s what happens in real L&D work:

- We spend time building “What’s your style?” quizzes instead of tightening our examples.

- We create three versions of content—visual, audio, and kinesthetic—instead of creating one clear, well-designed flow.

- We talk about “styles” in stakeholder meetings instead of talking about spacing, practice, or how this connects to real work.

The problem isn’t that learning styles are evil.

The problem is opportunity cost.

Every hour we invest in a model that doesn’t add value is an hour we don’t spend on things that do.

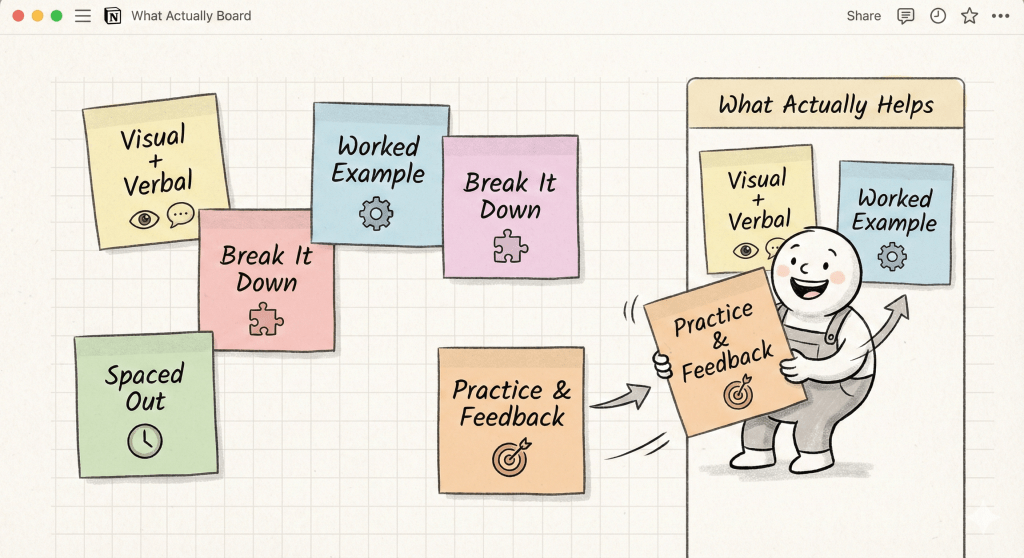

So What Should We Do Instead?

The good news:

We are not starting from scratch. Learning science has a lot to offer us here.

We have decades of evidence for strategies that help most learners, across jobs and contexts, without trying to label them.

Here are a few of the heavy hitters.

Combine Words and Visuals (Dual Coding)

People tend to learn better when we pair clear visuals with clear words.

A simple diagram plus a short explanation.

A screenshot with a brief, focused caption.

A process map plus a short story that walks through it.

Not decoration. Not stock photos.

Visuals that actually carry meaning.

Use Worked Examples

Before you ask a novice to “jump in and try it,” show a complete example.

A finished email with comments on why it works.

A full call script with callouts for each step.

A solved problem with the thinking made visible.

Research shows that worked examples reduce overload and help people build mental models faster than throwing them into full problems too soon.

Manage Cognitive Load

Our learners aren’t broken. Their attention is just busy.

You can help by:

- Making one key point per slide.

- Cutting cute but irrelevant details.

- Removing extra animations and noise.

- Using plain language instead of jargon.

You don’t need a style label to do this. You just need to respect the limits of working memory.

Use Spaced and Retrieval Practice

Cramming feels productive. It’s not.

Two simple shifts make a big difference:

- Spaced practice: Spread learning over days or weeks instead of one long hit.

- Retrieval practice: Ask learners to recall information (mini-quizzes, quick scenarios) instead of only re-reading or replaying.

Meta-analyses on practice testing and spacing show reliable benefits for long-term retention. They’re not flashy, but they work.

How to Talk About This Without Shaming Anyone

Here’s the most important part for our field culture:

Most people who use learning styles do it because they want to help.

So when you talk about this with stakeholders or peers:

- Assume good intent.

- Aim for curiosity, not “gotcha.”

- Focus on the upgrade: “Here’s something that works even better.”

You don’t have to call anyone out. You can simply say:

“The research on learning styles never really held up. Instead of investing in that, we can use strategies like examples, visuals plus words, and spaced follow-ups that have a much stronger track record.”

You’re not taking something away.

You’re offering an upgrade.

The Bottom Line

Learning styles feel intuitive and kind. They give us labels and the illusion of precision.

But large reviews—from Coffield and colleagues, from Pashler and others—keep telling us the same thing: matching instruction to a preferred style doesn’t reliably improve learning.

The real opportunity is not arguing about who is a “visual learner.”

It’s designing for how learning works:

- Clear, meaningful visuals plus words.

- Worked examples before solo practice.

- Spaced and retrieval practice.

- Respect for cognitive load.

You don’t need a style quiz to do that. You just need to shift your time and energy away from labels and toward strategies that actually pay off for your learners.

Future-you—and your learners—will be glad you did.