How Dual Coding Theory Explains (and Fixes) Your Biggest Learning Design Problem

Your learners look glazed over. They’re reading ahead while you talk. Or they’ve checked out entirely.

You know what they’re doing? Choosing.

Read the slide or listen to you. Not both. They can’t. And it’s not their fault—it’s your design.

Your Brain Processes Information Through Two Separate Systems

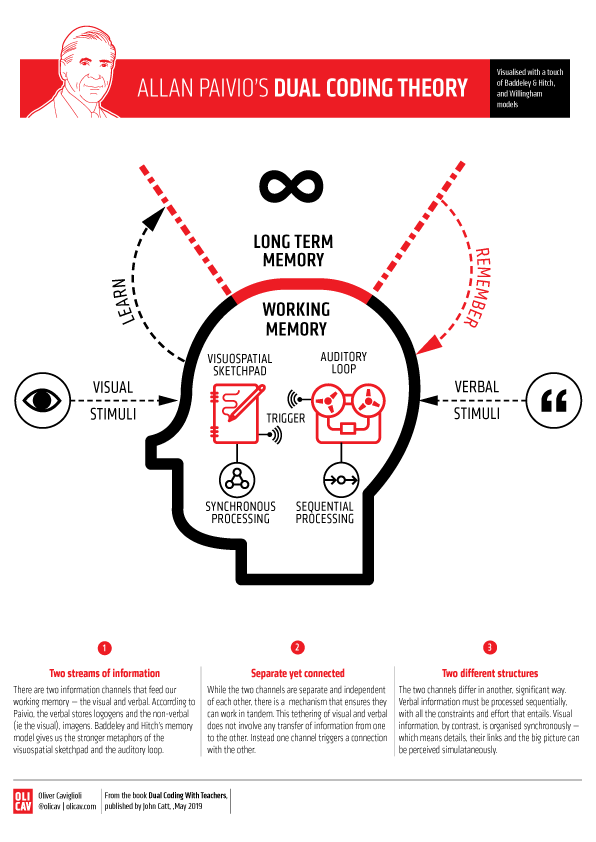

In 1971, psychologist Allan Paivio proposed dual coding theory. The core insight: your brain has two distinct processing channels. One handles visual and spatial information—images, diagrams, animations. The other handles verbal information—language and words.

The critical detail most people miss? It’s not about eyes versus ears.

Text on a slide gets processed through the verbal channel, even though you see it with your eyes. Your brain recodes written words into linguistic form. So when you put bullet points on screen and read them aloud, you’re forcing the verbal channel to process identical information from two sources simultaneously.

Think of two conveyor belts feeding into working memory. One carries visual representations. The other carries language. When each belt carries complementary information, learning compounds. You get multiple retrieval pathways, stronger encoding, better recall.

But pack identical information on both belts? The system jams.

Richard Mayer’s multimedia learning research confirmed this. People learn better from words and pictures together than from words alone—but only when those words and pictures complement rather than duplicate each other.

The Redundancy Trap

Most training designers make the same mistake: text on slide, narration reading that text.

You’ve seen it. Probably done it.

The problem isn’t repetition for emphasis. The problem is cognitive cost. Your verbal processing system has limited capacity. Force it to handle the same information from two sources—reading and listening—and you max out that capacity on redundant processing. No room left for understanding.

This is the redundancy effect. Your learners have to choose: read or listen. They read faster than you speak, finish the slide, then wait. You’re talking to people who’ve mentally moved on.

For novice learners especially, this matters. Experts can handle more complexity. But people learning something new need clean separation between visual and verbal channels.

Dual Coding Done Right

This BrightCarbon video demonstrates the difference perfectly.

First, they show the problem: slides packed with text while narration repeats those exact words. Then they flip it. Visual sequences—diagrams, animations, process flows—paired with narration that explains rather than repeats.

Watch how it works. The visuals aren’t decorative. They’re not self-explanatory either. You need both channels. What you see plus what you hear creates the complete understanding.

That’s dual coding working as designed.

Redesigning Your Materials

Stop treating slides as a script. They’re a visual partner to your narration.

Instead of bullet points repeating your words:

Show diagrams illustrating relationships. Use process flowcharts while you walk through steps verbally. Display before/after comparisons while you explain what changed.

Instead of definitions on screen:

Show examples or illustrations while you speak the definition. Visual representation through the eyes, explanation through the ears.

Instead of spelling out your message:

Let visuals do visual work and narration do verbal work. Explaining why customer complaints spike in Q4? Show the graph of complaint volume over time. Don’t write “complaints spike in Q4” on the slide. Your words explain why. The visual shows what.

The principle: related but distinct information through each channel. They support each other, don’t duplicate.

Try This

Find one slide where you’re reading on-screen text verbatim.

Remove that text. Replace it with a visual—diagram, icon, image, data visualization. Practice delivering it with the visual carrying its message while your narration carries yours.

You’ll know it works when the slide alone doesn’t tell the full story and your narration alone doesn’t paint the full picture. Together, they create understanding neither could achieve alone.

That’s how your learners’ brains want to process information. Stop fighting it.

References:

- Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and Verbal Processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Paivio, A. (1986). Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach. Oxford University Press.

- Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149-170.

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia Learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.